Motives In The Mountains (Part 2)

Posted by Jeremy Windsor on Jul 10, 2020

The reasons why we choose to climb are sometimes hard to fathom. As we were reminded in Part 1 the urge to spend time in the mountains can often come from a need to cope with the difficulties of day-to-day life. Whilst this can provide respite and help heal wounds, there is the potential for mountains to be a distraction and in some cases lead to unhealthy risk taking behavior. These thoughts were never too far from me as I read Crazy Sorrow by Grant Farquhar. Subtitled “The Life And Death Of Alan Mullin†the book pulls together the subject’s own writings and those of the wider climbing community in an attempt to understand the suicide of one of the country’s leading winter climbers at the age of just 34. Despite being abused in childhood and suffering the disappointment of injury and a medical discharge from the army, Alan was able to climb at the very highest winter grades within a couple of years of soloing his first grade 1 gully. The journey, carefully described in the book, picks out many of the factors that motivated Alan and the impact of his actions on those around him.

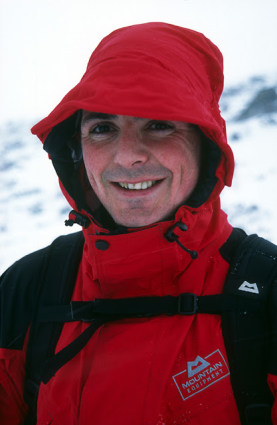

Alan Mullin (Photo: Ian Parnell)

Alan was perhaps best known for his audacious solo winter ascent of Rolling Thunder (VIII 8), an overhanging and poorly protected E3 rock route on Lochnagar. Summing up his effort, Simon Richardson, one of the UK’s leading climbers and a former president of the Scottish Mountaineering Club, wrote,

The impact of his routes on the Scottish winter climbing scene was electric. Mullin had arrived on the scene with very little climbing experience. It would normally take years of experience to acquire the spectrum of skills necessary to climb high standards winter routes, so how could a relative newcomer operate at the highest standards of the day? The answer partly lay in Mullin’s fitness and rigorous training regime, but mainly in the total focus and unswerving determination he applied to his routes. Other climbers soon realised that they could push their own standards too. Within a couple of seasons, average standards had jumped a level and grade VII, which was previously held to be the preserve of the elite, quickly became accessible to many.

We asked Grant, a practising psychiatrist and accomplished climber, to tell us a bit more about the origins of the book and the life of its extraordinary subject. Can I start by asking you what it was that led to you writing “Crazy Sorrow�

About 5 years ago I was crippled by a flare up of psoriatric arthritis and wasn't able to surf or climb so I was seeking a creative outlet. This led to me writing a book about Gogarth called The White Cliff which was an enjoyable process and then I was looking for another project. Crazy Sorrow was a good fit for me because it combines two of my passions: climbing and psychiatry.

What do you think it was about winter climbing that drew Alan to the sport?

He experienced it in the army in South Georgia and realised that he was good at it, and in his words: 'It's pure fucking mental'.

Simon Richardson talks about Alan’s “total focus and unswerving determination†that allowed him to make such a swift and extraordinary progression through the climbing grades. What do you think underpinned that?

Climbing provided, for a time, the meaning of life for him. For me, the cardinal problem in people like Alan who have borderline personality disorder (BPD) is what the DSM describes as 'chronic feelings of emptiness'. It doesn't sound that dramatic in DSM, but this is the precursor to suicidality: life has no meaning, what's the point etc so I might as well kill myself...

Alan on the first ascent of Crazy Sorrow (IX 10). He described it as, "a poorly protected 35m trad E4 6a in summer. In winter it transforms into thin mixed climbing on a steep 80 degree slab with rubbish gear in flared grooves filled with thin ice. It is the most committing climb imaginable and a fall from the difficult crux would undoubtedly have resulted in a broken back" (Photos: Steve Lynch).

As medical professionals we tend to place a lot of importance on someone’s diagnosis, but clearly there’s a lot more to a person than just their disease. Did Alan’s BPD play a large part in his decision to devote so much to climbing or were there other factors at play?

Great question: when we are engaging with our clients we tend to be focused on the diagnostic relevance of the psychopathology - the form - whereas the clients are focused on the narrative - the content. We have to be careful to ensure that we are having a conversation with the person rather than their mental illness. Alan's endless and fruitless search for meaning, due to BPD, took him on a journey through many places including the army, family life, drugs, fighting and climbing. Of course, climbing is great fun and a therapeutic activity for mental health and Alan was also exceptionally talented at it. Not everybody who climbs is mentally disordered, apparently, but Alan was driven by his demons to the extreme degree that he would actually vomit through fear on routes which is highly unusual. So, yes, I think that it was a driving factor in his climbing.

We often think of those with a BPD as lacking a degree of emotional empathy but we see in his writing real insight and thoughtfulness. Did this surprise you? Were you surprised by how well he wrote?

One of the features of BPD that I have observed in my clients, that I have never seen described in the medical literature, is hypergraphia - many of them tend to diarise and write about themselves a lot and bring or send me the writings to read. This is described in the literature in connection with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy as Geschwind Syndrome but has not been documented as a feature of BPD. I cannot place much validity on my anecdotal observation, but I was not surprised when I managed to unearth his writings. However, what you read by him in the book has been heavily edited. The original manuscript, I suspect, was written during a state of hypomania and is difficult to read.

You write towards the end of the book that climbing was a “therapeutic activity†for Alan. How did it help?

Research into the benefit of climbing as an experiential therapy for adults and children with mental disorders including, but not only, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, ADHD, trauma and addiction is growing. This will probably come as no surprise to many climbers who have already found these benefits for themselves. I'm providing climbing therapy as an experiential therapy in Bermuda. More information can be found here.

Andy Kirkpatrick's revealing portrait of Alan Mullin. Andy's fascinating tribute to him can be found here

You describe in detail the final months that lead up to Alan’s suicide. This includes the impact of chronic injuries, episodes of substance misuse and the new diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder. There is a real sense that many feel that Alan was let down by mental health services in Scotland. What would it have taken to prevent Alan’s death?

One of the problems with mental health services is that they become focused on secondary risks ie the risk to the organisation of reputational damage or legal action if there is a negative outcome rather than focusing on the primary risk (to the client). So they become risk averse and focused on risk assessment which is something that the science tells us is something we cannot do reliably and is therefore a waste of clinical time. Instead we should be using our clinical skills and time to provide excellent care and treatment for: Every. Single. Patient. Who is in distress and seeking treatment.

At times your book describes a man who seems remote and difficult to get to know, perhaps even hostile. After writing the book do you think it’s easier to understand him through his writings than face-to-face contact?

Although we were contemporaries, I never met Alan. However, we have many (climbing) friends in common and I suspect that he and I would have got on very well. Or maybe he would have battered me. Who knows? At least it wouldn't have been boring!

Grant has produced an incredibly poignant book that deserves to be widely read. By revealing the very complex nature of one of the UK’s finest winter climbers he also helps us understand the very complex relationship we all have with the mountain we love.

Crazy Sorrow - The Life And Death Of Alan Mullin can be bought here.

Part 1 of Motives in the Mountains can be found here.

Comments

Leave a comment.

Leave a comment.

)

)