The Moth And The Mountain

Posted by Jeremy Windsor on Feb 25, 2022

Ed Caesar’s new book, “The Moth and the Mountain” tells the story of Maurice Wilson and his solo attempt to climb Mt Everest in 1934. Here’s psychiatrist and DiMM holder Tony Page to tell us all about it…

The Moth and The Mountain is the story of Maurice Wilson, decorated war hero, long-distance aviator and prime mover in what could be described as one of the early British Everest expeditions. Heard of him? I hadn’t until I read Ed Caesar’s book. Born in Bradford and son of a self-made textile company boss, Wilson was a second lieutenant in the First Fifth Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment. He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions at Wytschaete in Flanders in 1918, when a few days after his 20th birthday he stayed at his post under heavy fire and delayed the German advance. Three months later he was injured in his back and left arm by machine-gun fire and did not see active service again.

Wilson set off for Mt Everest aboard his Tiger Moth - nicknamed "Ever Wrest" - on the 21st May 1933. Despite little flying experience, a lack of maps and a telegram from the Air Ministry forbidding his journey, he arrived safely in India two weeks later!

Wilson had a complicated love life. He married in 1922 and the following year left for New Zealand with his youngest brother Stanley, but without his new wife. She joined him in 1924 by which time he had fallen in love with another woman. His wife divorced him and he married again in 1926. Following his second wife, a successful businesswoman, on a business trip to north America, Wilson linked up with a married woman on board ship and the two of them travelled in Canada and in the US together. However, they went their separate ways and Wilson returned to Yorkshire, moved to London and in 1931 sailed for Durban, South Africa. On the same ship was a young dress designer from London who, six months later, returned to England from Mozambique on the same ship as Wilson. Coincidence? Caesar suggests not, but the two seem not to have continued whatever relationship they had. Instead, Wilson developed an infatuation with Enid Evans, the wife of a man he’d met at work. The relationships between the three was complex, and latterly that between Wilson and Enid was epistolatory. Strangely, this seemed to strengthen it, certainly so far as Wilson was concerned.

In the aftermath of the war and, Caesar suggests, perhaps as a consequence of its horrors, various spiritualist and occult ideas were circulating. An avid reader, Wilson had been developing an idiosyncratic religious syncretism that included the beliefs that he could make himself strong through fasting and prayer and that with sufficient faith, anything was possible. It was in this context that, in 1932, he read a newspaper article about the 1924 Everest expedition and conceived the idea that he would climb Mount Everest - alone. Not only that, he would fly himself from England to Nepal. The facts that he had no mountaineering experience and was not a pilot were simply problems that he would have to overcome.

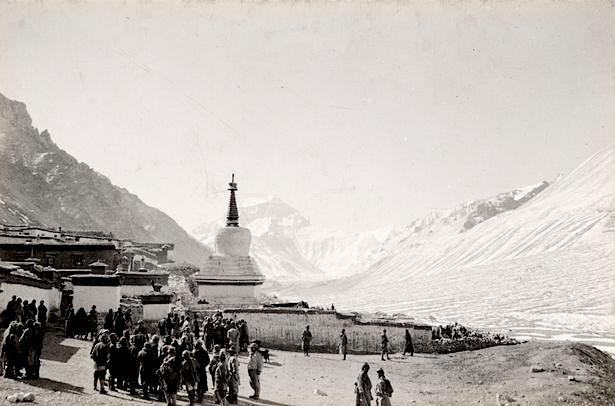

Over the course of the next 9 months, Wilson travelled through India and Tibet, eventually arriving at the Rongbuk Monastery on the 14th April 1935. Using equipment left by previous expeditions he set off immediately and was able to reach a high point of just under 7000m. Unfortunately, bad weather and steep ground hampered any further efforts and he returned to the monastery 2 weeks later

The rest of the book tells of his mountain training - long walks in the Lakes and in Snowdonia (no practice using axe or crampons, no glacier crossings, no visit to the Alps), his purchase of a Gypsy Moth (the Moth of the book’s title), his flying lessons in Edgeware and his epic solo journey from London to Lalbalu in India in the face of opposition from the authorities, culminating in his attempts on the mountain, where he reached the slopes below the North Col. He died on his last attempt in May 1934, probably of hypothermia. Of course, his expedition was never taken seriously by the mountaineering establishment and as it was unofficial and not a large, nationally organised venture it was relegated to the footnotes of the history of Himalayan mountaineering. Today, we might consider it way ahead of its time, though Wilson did not have the skills, equipment or experience to execute it successfully.

The story has a parallel interest for the mountain medic, or at least for those who have an interest in psychology and psychiatry. Wilson’s older brother Victor was also a war veteran and Caesar’s account makes clear that he suffered from a severe form of combat-related psychological trauma. Wilson himself made a good physical recovery from his wounds, but complained that his skin was tender to touch, that pressure round his torso caused severe pain such that he could not even wear braces. His courage is not in doubt but, like his brother, might he too have suffered from combat-related psychological trauma, albeit a less severe variant? What of his restlessness and inability to settle into a relationship? What of his eccentric spiritual beliefs? He would have read the reports and probably some of the first-hand accounts of the earlier expeditions and would have had some idea of the difficulties involved. What of his conviction that through fasting, faith and prayer he could climb Everest alone? Could we classify this as delusional? Could it be an example of what psychopathologists would call an ‘overvalued idea’? Certainly, he went on to act on his conviction with an unwavering determination.

Despite the pleas of his Sherpas, he returned to the mountain for one last effort on the 29th May 1934. He was not seen alive again. Wilson's body was eventually found amongst the remains of a tent by members of the 1935 British Mt Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. Although the cause of death will never be known it's likely that hypothermia, dehydration and hypoxia would have played a part

Sensibly, Caesar avoids suggesting answers to the questions of Wilson’s mental health, leaving it up to his readers to form their own opinions. In this context it is worth remembering that combat-related trauma was understood and experienced differently at the time, and that post-traumatic stress disorder, as we now understand it, could not have been conceived before the Vietnam war. Wilson’s motivations were complex and perhaps not related to combat-related psychological trauma, and Caesar tells his story with sympathy and aplomb. The book fills an historical gap and I found it intriguing and even exciting, though the eventual outcome was not in doubt. The book has been shortlisted for the 2022 Costa Biography Award and it would be a worthy winner!

Thanks Tony!

Tony has written a series of brilliant posts for this blog - why not take a look at what he's got to say about managing risk in the mountains, achilles injuries and his experience of lockdown! Tony's description of depression and its management can be read here

Comments

Leave a comment.

Leave a comment.

)

)