A Mountain Master...

Posted by Jeremy Windsor on May 19, 2023

Earlier this year Dr Chris Lewis was amongst four students who were awarded a MSc in Mountain Medicine by the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan). We caught up with Chris to tell us about his background and the process of completing this much sought after qualification...

Thanks Chris for agreeing to speak to me. Before we start - congratulations on being awarded your MSc in Mountain Medicine! Before we talk about it, can I ask you to tell us a bit about yourself?

Thanks, Jeremy – kia ora!

I’ve recently emigrated to the South Island of New Zealand where I’m working as an anaesthetics registrar. I’ve wanted to explore the country since I was a student and it’s great to be gaining some training and experience in a different healthcare system. It would be misleading of me to deny the increasing push factors, too. There’s a huge contingent of Brits over here, sometimes described as ‘NHS refugees’.

I completed the academic foundation programme in the Scottish Highlands and used my non-clinical time towards the Diploma in Mountain Medicine (DiMM). After an FY3 year, I landed the dream job – an Anaesthetic / ITU / Mountain Medicine clinical fellowship at Ysbyty Gwynedd, Bangor. It was a privilege to spend two years at the hospital, learning from inspiring colleagues and living on the edge of Snowdonia. I don’t really buy into rotational training and have been incredibly fortunate so far in piecing my own career pathway together. For anyone considering this approach – despite sounding quite glamorous, the administrative challenges are not trivial. Be warned!

Outside of work I was involved in training and assessing candidates on the Mountain Rescue Casualty Care Course, which represents an extraordinarily impressive standard of ‘lay person’ first aid. I joined the DiMM faculty in Switzerland last year. My personal climbing background included one or two torchlit starts in Scotland, some time in the Alps, a couple of 6000m summits and a recent first ascent in Tajikistan.

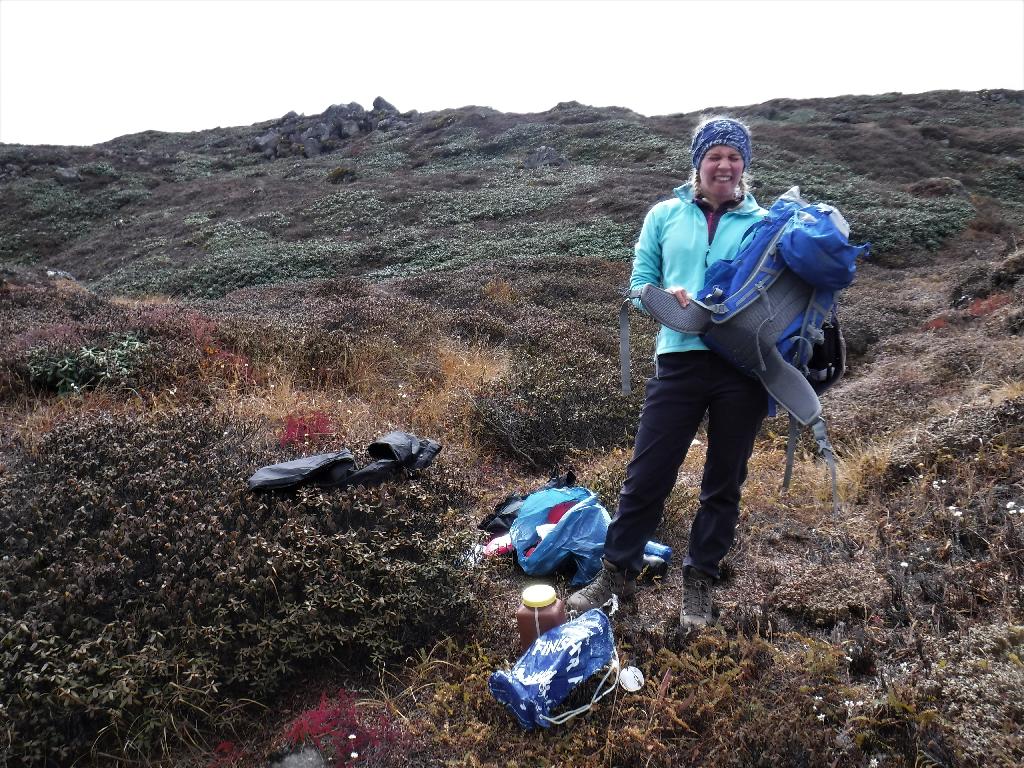

Chris Lewis in Tajikistan. Photo – Alex Metcalf

What led you to decide on a MSc in mountain medicine?

I’m a bit of a nerd. As a medical student I was bribed into academia by various travel scholarships, and published my intercalation project. At the same time, I became involved with the Birmingham Medical Research Expeditionary Society (BMRES) joining several high altitude research expeditions and gaining valuable experience of field data collection in remote places. I owe a huge amount to the mentorship and support I have received through the group.

The DiMM’s recent move to UCLan, the result of an extraordinary amount of hard work from some truly dedicated individuals, opened the possibility of an MSc. My contract at Ysbyty Gwynedd included funding for the course and ensured that I had some study leave to complete it, enabling me to maintain some academic momentum whilst also progressing my clinical career. I already had some project ideas for an upcoming BMRES research expedition, and it seemed like an efficient use of time to use the work towards my dissertation.

Mt Blanc de Cheilon, with the Diploma in Mountain Medicine. Photo - unknown

Can you tell us about your area of research?

Many readers will recognise the phenomenon of ‘peeing like a racehorse’ (diuresis, in medical parlance) on ascent to high altitude. It has been established that people with a blunted diuretic response seem to be more prone to developing acute mountain sickness. However, renal adaptation to hypoxia is incompletely understood. The project explored changes in urinary electrolyte excretion on ascent to high altitude.

I was a fortunate recipient of the BMMS “Lucky Jim” Award in 2021 and enjoyed reading and referencing many of Jim's original papers whilst writing my thesis. I was reminded of how fortunate I was to hear him speak about his exploits when I first started the DiMM – his passion and energy was infectious, and his pioneering work on high altitude physiology remains incredibly relevant.

Field research in Sikkim. Photo – unknown

How did you collect your data? What were you collecting?

The data came from a BMRES expedition to Sikkim, India, in 2019 (more about this below).

During the expedition, we undertook daily 24-hour urinary collections during ascent to Kangchenjunga Base Camp (around 5000m). Pissing into a bottle when you’re tired and hypoxic, and carrying up to four(!) litres of urine in your rucksack every day for almost two weeks, is about as glamorous as it sounds. The female members of the party demonstrated particularly impressive skills here. Astonishingly, we only had one catastrophic spillage within the group. As every member of the expedition party was involved in some sort of research project, there was outstanding dedication to each of the experiments. I don’t think a study like this would be feasible without such collective buy-in. A proper team effort.

Each day at 4pm, the group would empty their bladders and hand in their warm bottle(s). We weighed each sample, gave the contents a good stir and then pipetted several specimens into test tubes for storage on dry ice and return to the UK for biochemical analysis. The logistics behind the operation were really quite remarkable. We also collected various other data along the way including Lake Louise Scores, physiological measurements, and some blood samples.

Urine mishaps in Sikkim! Photo – Chris Lewis

What were your findings?

The article is being tidied up for peer review and will hopefully be submitted shortly. You’ll have to read the paper!

What were the most challenging parts of your dissertation? How did you overcome them?

Covid-19, Brexit and climate change all caused very tangible disruption – a sign of our times. Firstly, the research trip originally planned for Annapurna, Nepal, in 2021 was delayed for a year due to pandemic-related travel restrictions.Then, we were unable to get hold of a key piece of equipment from the EU, leading to a complete project re-design. And finally, when we eventually arrived in Nepal in October 2022, a severe weather event meant that the studies were no longer feasible. Data collection was completely abandoned. Devastating.

Fortunately, while waiting for the weather to improve in Pokhara, I had an unexpected opportunity to interrogate some un-analysed data from the previous expedition. These proved to be rather interesting and formed the basis of my write-up. It was a rare privilege to have several days of uninterrupted time to explore the data, with subject experts on hand for advice and discussion.

North Wales is renowned for its mountain crags. Photo - Tom Smith

Although completing the dissertation required some flexible thinking and dynamism, as well as a huge amount of support from my supervisors, I think the most challenging part of this whole process for me has been coming to terms with the very obvious planetary changes that are increasingly impacting our lives. Following last summer’s dire alpine climbing conditions, and the sad state of the glacier and erratic weather we encountered in Tajikistan, the late rains in Nepal added to the endless litany of ‘unseasonal’ and ‘unprecedented’ weather events causing disruption across the world. I have been left grappling with my own responsibilities and mountaineering identity.

Like many people, I’m a bit stumped. I acknowledge there’s a spectrum of opinion here, from “We just need to be prepared for unpredictable mountaineering conditions” through to “The planetary impact of aviation is unjustifiable” – and more extreme views on either side of that. I left Nepal last autumn wondering if it would be the last time I set foot in the Himalayas. I am grateful for the huge privilege of having spent some time in the greater ranges, but will need some really robust justification (or a bicycle and a long sabbatical) to return again.

I suppose the handy thing about the UK is that there are some awesome domestic adventures to be enjoyed, and much of Europe is pretty accessible without needing to fly. I found that travelling by public transport to and from the Alps last summer was far less stressful than fighting the massive airport queues, with considerably less baggage jeopardy and made the journey feel much more like an adventure!

UK mountaineering has plenty to offer: Tom Smith on the Liathach Traverse. Photo – Chris Lewis

What advice would you give to those who are thinking about a MSc in mountain medicine?

The progression from PGDip to MSc focuses very much upon research methodology, study design, data analysis and academic writing. The taught module is quite generic and its contents will be reasonably familiar to anyone with experience in academia, such as through intercalation or publishing research. The dissertation requires a project idea and a bit of self-motivation. The course is delivered remotely – I’ve never even visited the UCLan Campus!

I was fortunate to have some outstanding supervision to help navigate the various mishaps, without which I think I might have withdrawn from the course. Notably – the indefatigable Dr. Sam Lucas provided academic support and great chat. The time difference between the UK and New Zealand facilitated some astonishingly efficient amendments to the dissertation as the final deadline approached.

Sea cliffs on Skye. Photo - Lucy Hall

I’m also incredibly grateful for the guidance of Dr John Delamere, whose decades of high altitude research experience and robust understanding of renal physiology were invaluable, and to Dr Beth Hall-Thompson who somehow managed to smooth everything over with UCLan and kept things running to academic deadlines.

Undertaking any post-graduate qualification alongside a full-time clinical rota represents a decent commitment. It definitely nibbled into my free time, although I completed some of the course during the 2020/21 winter lockdown when the opportunity cost was a bit lower. So if you’re hoping to balance full time work with an MSc, studying for professional exams, training for some sort of athletic endeavour and maintain some sort of social life think carefully about your priorities and be prepared to compromise. You might be able to pull it all off – there are plenty of superhumans in our cohort… but I’m not one of them! (I chose to sacrifice the FRCA Primary as I was never planning to stay in the UK.)

The UCLan website gives some information about the course.

I’d be delighted to hear from anyone interested in finding out more – please get in touch with me through the blog.

Well done Chris! Thanks for sharing your experience. I'm sure it will encourage others to think about a MSc in mountain medicine!

Thanks for reading this post. If this is your thing why don't you take a look at other posts on the blog? Better still, why not join the British Mountain Medicine Society? More information can be found here

For more information about the University of Central Lancashire's Diploma in Mountain Medicine (DiMM) take a look at this.

Comments

Leave a comment.

Leave a comment.

)

)