"An Incurable Optimist" Part 2

Posted by Jeremy Windsor on Mar 14, 2025

This is the second of two posts that focus upon the climber and mountaineer Iain Peters and his extraordinary new memoir, "The Corridor". In Part 1, Tony Page reviews the book and concludes, "Though it is at times an undeniably uncomfortable read, it is also a frank, moving, and ultimately hopeful testimony. I strongly recommend it". In this post we hear from the author himself. In the lead up to the interview Iain stressed that there shouldn't be any "no go areas"and so we've focused upon the sexual abuse he suffered and the impact this has had upon his life.

Thanks Iain for talking to me. When we first got in touch you sent me a video clip of a Channel 4 news report that described the process that led up to the successful prosecution of the man who sexually abused you as a child. Watching you speak was incredibly moving. I cannot imagine how difficult that was to do. Can you tell us about what led you to putting yourself in front of the camera? Was this the starting point for the book?

No, the starting point was walking into a police station on the spur of the moment after I had pulled out from my pocket a description of being raped that I had written instead of a shopping list! The police investigation took about two years before John Earle was arrested following approval to prosecute from the Crown Prosecution Service. I had continued to write the book throughout the period as well as including my own analysis from counselling. Obviously the police did not want any publicity at this point as it was only after Earle had changed his plea to guilty on six counts that I realised I would have to forego my anonymity if I wanted my voice and experience to be added to others. My wife Ellen had an old friend who was a radio reporter and she suggested that we should contact C4, if I was prepared to tell my story in public. The actual interview was one where the usual British stiff upper lip was replaced by raw emotion. For someone who had spent a lifetime in denial, dissociation and deceit, there was suddenly no hiding place, no escape, a sense of a door opening at last.

Can I ask whether you spare any thought to what your life would have been like without the sexual abuse you suffered?

Yes and no! Over the years of silence I do remember occasions when I envied friends who had good jobs, mortgages, smart cars, pensions and the trappings of success. Somewhere in the book I mention being outside and looking through a window at life inside and feeling isolated, but at another time feeling trapped being on the inside and looking out. Life is full of contradictions as well as compromises, but maybe heightened in my case. Now, having disclosed and spent so long in my own company when writing the book, the ‘what if’ thoughts have receded, replaced by the realisation of how it is possible to feel happy and fulfilled in the present despite recognising that past pain and grief cannot be ignored.

Iain Peters enjoying life in his 70's

Are there any limits to the shadow the abuse has cast across your life? How can you tell what parts of your life were affected? Are there areas that you can say most definitely - this is just me and not the abuse that I experienced or is it all linked together?

That’s a hard one to answer and would be for any individual however balanced and fulfilled their past life has been. Rape casts a very long shadow, one that can swallow a life as it did for my dear friend and fellow victim Keith Brooks who became addicted to drugs and suffered from mental illness throughout his life. In my case, I had a happy and loving early childhood and a grandfather who became both mentor and friend, both remained there in the subconscious. But yes I was a rebel long before the abuse, and almost certainly would not have stayed on the so called straight and narrow. Some of my life decisions can’t be put down as a consequence of rape, although perhaps were exaggerated by the experience. Rebels will, by their nature, take bigger risks that can easily end in failure or make palpably wrong decisions.

Can I ask you about talking to your family about what you suffered? How do you start the conversation? What did you want from them when you shared it?

I never said a word about the abuse to anyone, for over 50 years. When the floodgates opened with the police investigation and counselling around 2014 I discovered just how strong my first wife Amanda and the children were. Of course they were horrified, who wouldn’t be? Since then, there are occasions when we are all forcibly reminded such as when further revelations of abuse make the headlines or when the subject is raised in conversation. I can still cry when talking about it, but feel safe and supported enough not to hold back on my emotions: as to what I want from them when I share, the answer is very simple, there is no demand on my part, because they know and we love and trust each other.

However I realise that going public by writing the book, media appearances or interviews such as this may not be viewed with the same compassion and understanding as shown by friends and family. I stayed silent for far too long to even consider remaining so now.

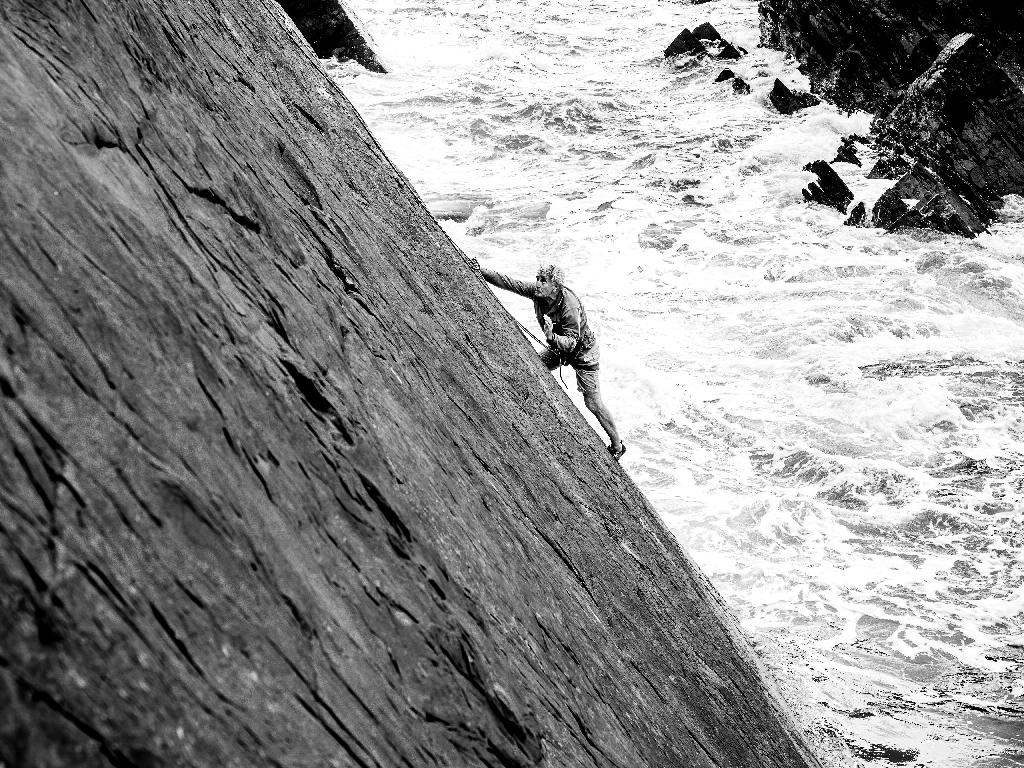

Climbing a new route with Dave Hillebrandt

You speak about a fear of ambition. If I understand rightly, this stemmed from a worry that you’d become an abuser yourself. Many thinking about the appalling nature of sexual abuse for the first time, may struggle to understand such a thought process, can you explain it?

Yes, incredibly complex. First and foremost, I have to say that rape is actually about the misuse of power that happens to be expressed sexually. I think I can safely say that my experience acted as very strong aversion therapy; so strong that it affected my intimate relationships, especially during and after completely consensual sexual activity. My natural dislike of systems and institutions was also exaggerated by the belief that success would lead to power and power to abuse in many other forms, raising the insidious question, “was I being abusive?” Far easier to reject success, even in the one physical and mental activity I loved so much, climbing. In my teens and early adulthood I knew I was strong and technically capable of climbing to a comparatively high standard, but somehow never committed to it in the way that many of my peer group did for the same reason.

Rape renders the victim helpless in the face of overwhelming power. Is this not at the very heart of how our society functions, or rather malfunctions today? I am not suggesting that our political leaders, captains of industry and powerful individuals in the professions are rapists, though some may well be, but there is real truth in the saying that power corrupts…

Do you remember how you started writing the book? Were there points where you hesitated or paused? What helped you to get writing again?

I guess it started with a grubby piece of paper which was the raw statement about the abuse I wrote at a time of great stress, then later handed to the police. I am naturally reasonably articulate so when I began to trust myself through counselling, I was able to speak more freely and then put down on paper much of what had been discussed. These sessions became the reflective or analytic passages of The Corridor, and in many ways, jump started the memories that then became the narrative.

Points where I hesitated? Oh God yes. There were periods of doubt and that’s when disassociation led to extreme procrastination. Perhaps there were three different jolts that got me going again.There was the loan of an isolated croft in the Outer Hebrides where I spent a month by myself with my dogs and a laptop before Ellen joined me. Next came lockdown in 2020 when we were confined to our homes. In my case, that meant solitude out on the north Devon and Cornwall Coast and an isolated hut, belonging to the family of the late poet and playwright Ronald Duncan, where I escaped to at dawn. Finally, it was the constant encouragement by Ellen not to give up. She called it nagging, and at times I rebelled, finding all sorts of excuses to avoid carrying on!

Gurnard's Head is the home of Iain's best known route - Right Angle (HS 4b)

Can you tell me about the anger you felt? You speak about thoughts of killing your abuser. This isn’t often voiced but must be a far commoner emotion than it might at first appear. What made you talk about it?

I think the anger came to the surface not so much in counselling which, for me, was more about the pain and grief, but during the writing. The fictional piece in the book called Asesinato arose from the moment on the first expedition to The Cordillera Darwin, when Earle had so pissed me off with his overbearing ego and incompetence as a mountaineer that it boiled over into fury at what he had done to me and others. Seeing him almost falling into a crevasse and helpless made me think that the solution and my revenge for his crime was literally in my hands. It passed, I pulled him out, but it would have been the perfect murder. After that incident my anger was replaced with utter contempt, a dawning recognition that this blustering fraudster was basically impotent. That was in 1979 so still nearly 20 years before any closure.

Handing the crime over to the police, telling family and friends, counselling and even the exposure of a TV interview was a massive help in my recognising that as a victim, I needed to move through anger and beyond to more positive ways of dealing with the issue.

Although not mentioned so far, there may be another question in the minds of those who know my story either from the interview, my verbal accounts or the book, which is; how could I bring myself to work for my abuser as the Chief Climbing Instructor at his Adventure Centre or even consider going with him on an expedition to remote mountains?

This question was the hardest one to face. Very early on when I was considering putting my life story into words I realised that there could be no holding back. For sure, I can acknowledge that the trauma of being raped for over four years had a huge impact on my subsequent life but my fall back positions of denial, disassociation and deception would work just as radical surgery may be a necessity to save one’s life. To begin to find an answer I put put this question to my counsellor and therapist. She responded by describing the 4 Fs as a recognised neurological response to sexual abuse by the victim, Flight, Fight, Freeze and Fawn: I recognised all 4 from my experience as a small child, but somehow the latter didn’t seem to fit with the issue I’ve raised in the question.

It would be too simplistic and easy to persuade myself as victim that my adult relationship with Earle was an extension of the desire to avoid further suffering by fawning. The answer I arrived at was far more complex and certainly contained elements of that other alphabetical sequence, the 3 Ds of Denial, Disassociation and Deception. It was easy to use all three to allow me to contemplate working with this alternative Earle, the rapist confined to my deepest subconscious. There was an additional incentive: I was a far better climber than he could ever be, that alone provided an illusion of power, in some strange way proof that he had not succeeded in destroying me as he had with Keith and others. Later, on a glacier in the Cordillera Darwin, I succeeded in convincing myself that I had finally beaten him. It was a pyrrhic victory but eventually led to an old, frail man being sent to gaol and a very real sense of a door that had stayed locked for so long finally opening at my touch.

Too often survivors have to find closure in their own inner resources, especially when imprisoned by the omerta code the rapist places upon them, strengthened by guilt and shame.

Your good friend Dave Hillebrandt said of the book that it was “more informative than any NHS online safeguarding course”. What messages should health care providers, especially those in training, take away from your experience?

Hmm. I asked Dave to elaborate; his response was interesting and possibly resonates with other care providers whether in or away from the mountains. He summed it up by stating that child protection training for GPs consists of dry, boring on line courses full of facts but devoid of emotions or personal feelings. It is also to some extent true that emotions and personal feelings may not be top of the agenda in the mountain environment. That said we have moved away from the tough "Muscular Christianity” approach that I experienced in the Outward Bound type training establishments in the 1960s.

Dave, pointed out that the salient features of The Corridor, as he saw it, were that sexual abuse can happen to anybody, as much to a privileged, middle-class, white kid as to a child from a deprived, different ethnic background. It is an extreme dissonance that ignores frontiers and barriers of all kinds. The victims are all around us, despite the invisibility that they feel they need to acquire as protection. Sadly, this is also true of the perpetrators, who are extremely adept at covering their tracks whether with the tacit collusion of large institutions such as religions, educational establishments or the World Wide Web and its latest manifestation AI.

Iain climbing at Screda Point close to his home in north Devon

Following my interview on C4 I was contacted by dozens of victims or their families who could not bear to disclose formally. I hope that my book as well as other media outlets and support organisations will help all those who work in the wider world of caring to create an atmosphere that can encourage people like me to share our suffering openly without shame, guilt or rejection.

It took me far too long to trust anyone, especially myself, enough to tell my story, so I would say to everyone involved in their work with their fellow human beings irrespective of their age, gender, skin colour and financial background, to create the necessary safe environment (whether it is up a crag, in a clinic, school or church) that encourages people like me to unburden ourselves if we so wish.

I hope my book can in some small way help reduce the stigma of sexual abuse.

Iain, can we finish on something completely different? Many reading this will have climbed in the south west of England. A good number will have climbed your brilliant route on Gurnards Head - Right Angle (HS 4b). If they haven't - they should! To celebrate 50 years since it was put up, you invited 50 friends and family members to climb it on a single day. What did it mean to you?

I guess it summed up for me how lucky I have been, not only to have found and climbed the route, nor to be able to get up it half a century later, but to be able to share my love of climbing, and by definition, life with my friends and family. That day in late summer nearly 10 years ago just reinforced that feeling. Now it's only just over a year to the 60th. Bring it on!

Thanks Iain.

Tony's review of "The Corridor" can be found here.

Copies of Iain's book can be bought here.

If this is your sort of thing why not take a look at other posts on the blog?

Better still, why not join the British Mountain Medicine Society! More information can be found here.

For more on the University of Central Lancashire's Diploma in Mountain Medicine take a look at this.

Comments

Leave a comment.

Leave a comment.

)

)