Swung Out From Under My Feet

Posted by Jeremy Windsor on Feb 3, 2023

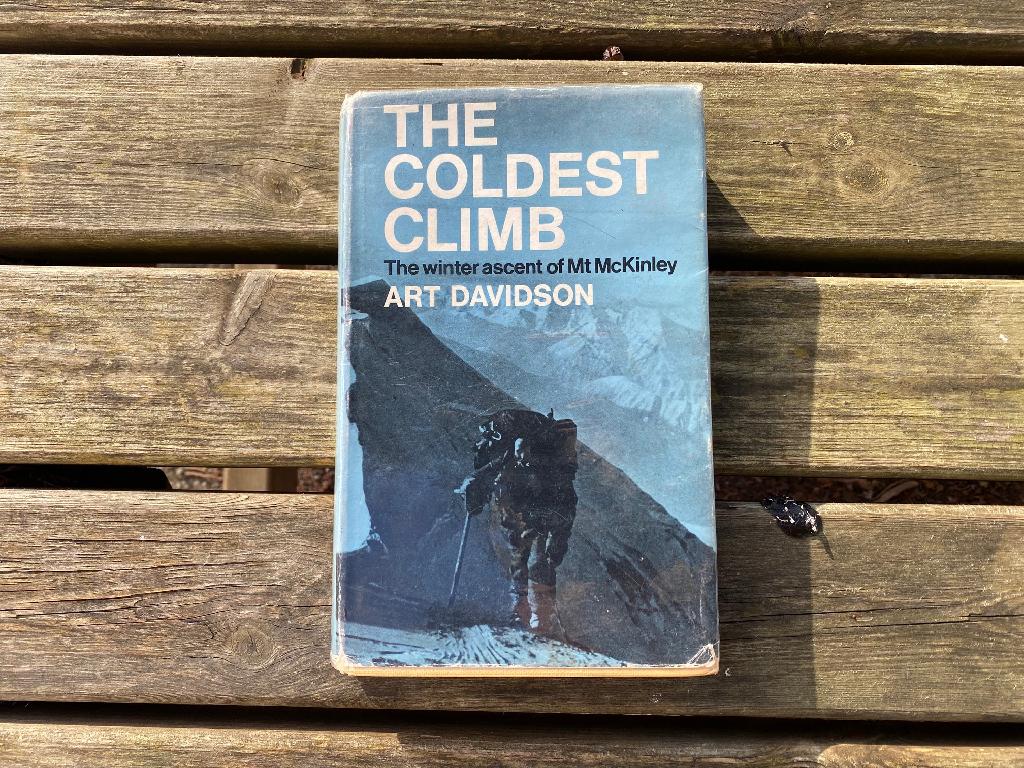

In January 1967 a team of 8 mountaineers attempted the first winter ascent of North America's highest mountain - Denali (6190m). After weeks of preparation, their progress was stalled at 5240m when one of them developed Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) and possibly, High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). However a short descent to 4390m, resulted in a dramatic improvement in symptoms. This extract from "The Coldest Climb" by Art Davidson highlights just how much a small descent can make to even the most life threatening of conditions...

I slept poorly, and the tossing I heard through the night indicated that the others were also managing to get only short spells of fitful sleep. I was wakened by a gentle rattling of pans; Shiro was starting breakfast.

Our camp came to life more quietly than ever before. After our usual yawns and questions about the weather we sat silent over our oatmeal. The altitude had been working away at us during the night. No one was well rested. We had no energy to spare for joking and idle conversation.

The first person out of the cave shouted back that it was too windy for a summit attempt. The weather we feared most was the violent wind, which can rise within an hour's time from a gentle breeze. When masses of wind begin blowing over Denali some wind is always forced through the passes and cols at velocities which have been reported at 150mph and more. We were especially cautious about venturing out from high camp because only a thousand feet above, and right on our route, was Denali Pass, the most notorious wind slot on the mountain. Up high in winter even a 50 mph wind could destroy a climbing party, because at -50 degrees F a 50 mph wind creates an equivalent wind-chill temperature well below -100 degrees F. None of us had ever experienced conditions like that, but we expected that if the wind caught us above this camp there could be no retreat except to dig under the ice and sit it out.

Even if that morning had been calm, I doubt that anyone would have tried for the summit. We were simply too tired.

Until I left the cave to relieve myself there was nothing to do with the day but settle back into our sleeping bags to wait for a morning without wind. I crawled out from under the flap of parachute that covered our cave's entrance without and premonition of what was coming. As soon as I stood up the cornice swung out from under my feet and the sky seemed to break away from the earth's grip. I leaned against the rock column to keep from toppling over the edge and breathed deeply many times before my head began to clear.

I sat still till I thought all the dizziness had left me, then tried to swallow a vitamin pill. The stubborn capsule stuck part way down my dry throat, and in seconds I had spewed my breakfast onto the snow. My head began aching. I felt sweat on my forehead. Little waves of nausea swept over me and I decided to squirm my way back into the cave on my belly.

Art Davidson, Ray Genet and Dave Johnson completed the first winter ascent of Denali on the 28th February 1967. In the USA, Davidson's book was called "Minus 148 Degrees" - a nod to the -148F that the three men encountered on their descent from the summit

There was no need to discuss what had to be done; we had no choice. Everyone but Pirate and George prepared to descend. At 14,400 feet (4390m) I'd have a better chance to recuperate. As everyone hustled around me, I overheard someone say that if we didn't get off in an hour or two I might have to be carried down - I shuddered at the thought of being lowered down the ridge rocks and then the ice wall. Gregg decided that four people would be enough to get me down if I passed out along the way, and somehow it was decided Pirate and George would remain at our high camp so that at least two people would have a chance at the summit in case the rest of us never returned to this plateau. Hopefully, we'd be back up in two days, but there was no way of knowing.

Dejected, my head throbbing, I rested while the others hurriedly broke camp. I hated to think that I wouldn't be able to try for the summit myself. And, as my fears raced on, I pictured myself having to be airlifted off the mountain by helicopter. The worst torment was that the others were being forced to descend because of my sickness, my weakness.

To cheer me up John and Dave said they could use a rest at 14,400 feet themselves. Gregg, worried about his foot, told me he welcomed the chance to pick up more socks at the igloos. As Shiro shoved my things into my pack, he reassured me that a dingy night at 14,400 feet would clear up the type of altitude sickness I had. George added that he didn't think I was suffering from anything as serious as pulmonary edema, and that I would be fit to give the summit a try after a few day's of rest.

"Day after tomorrow," Shiro said "you'll be back here." He winked at me, "Everything is OK"

"You bet, Shiro." But I hardly believed it. I wanted to shrug off their reassurances, but at the same time I wanted them to comfort me.

We roped up, Shiro and Dave were on my rope; I went first. If I slipped, they would be behind to hold my fall. I stepped down over the rocks and ice much more slowly than I had coming up the other day. Whenever the ridge began swaying, I leaned against a rock or on my ice axe until my dizziness cleared away.

The ridge was the most demanding part of my descent. We edged our crampons from ice to rock to loose snow. My legs were unsteady. I concentrated on my balance and on where I'd next set down my boot. I crept along the snow ramps, which now seemed to be impossibly narrow catwalks. I accused the gusty breeze of trying to trip me up.

On arriving at 5240m, Davidson rested in a tent whilst awaiting the excavation of a snow cave. Once completed, he set off and later recalled, "As I walked the thirty odd yards to our new home I had to stop twice to rest. Since the ice was mostly level, I knew I shouldn't find it this difficult to cross over to the cave. Something was wrong with me. John spotted me panting and leaning against a rock; he asked how I felt. Muttering something about the fantastic view from this spot, I tried minimizing my dizziness." The next day would prove much worse...

Three or four times I asked Dave to secure himself and belay me over a tricky spot. I noticed his eyes following every movement of my feet. It was reassuring to know that his strong hands and arms were holding the rope.

We rested only a few minutes when we reached the col. Hastily, we clipped into the fixed ropes and continued down. Several hundred feet below the col I realised that the breeze was no longer prying at my balance. Already the air seemed to be thicker. I felt stronger. Perhaps it was only psychological relief that made me feel better; I was happy to be off the ridge.

Despite the rest that came every few hundred feet, our descent down the ropes was rapid compared to our travel on the ridge. All at once we were off the ropes and walking towards the igloos. Shiro got me into a sleeping bag. Dave passed me cup after cup of hot milk. I nibbled on some cheese and salami. Before the main meal was cooked, and before I had chance to sit back and worry about my chances of going up again I was asleep.

I didn't stir until laughter woke me around mid morning the next day. When I grumbled about the racket the others were making. Someone repeated Gregg's story about his first job; in a soap factory he had accidentally emptied a several hundred gallon vat of shampoo into a street, causing traffic to jam up behind a cloud of suds and bubbles.

I discovered I could laugh again, and, what's more it seemed that I'd been given a new body during the night. My head was clear; I could think faster than I had been able to up above the previous day. My muscles felt so good that when I stepped out of the igloo for a breath of air I had an urge to spring across the basin and back. After gulping down a huge breakfast, I became restless for action. No one was more surprised than myself that I seemed to have recovered from my bout of mountain sickness...

Read about the origins of high altitude medical kits here. What about cutting edge high altitude climbing in the 1970's or closer to home, Scotland's most enduring snow patches? Find these and other posts on this blog!

Thanks for reading this post. If this is your thing why don't you take a look at other posts on the blog? Better still, why not join the British Mountain Medicine Society? More information can be found here

For more information about the University of Central Lancashire's Diploma in Mountain Medicine (DiMM) take a look at this.

Comments

Leave a comment.

)

)